02/10/2024

Sadbh O’ Brien—The Master of Noise

Every Monday at around 9:15am my phone buzzes with my weekly Screen Time Report offering me insights into my phone usage. Yesterday, I spent 4 hours 17 minutes on my phone and picked it up a total of 158 times. I trick myself into thinking I am doing well—the average daily screen time for an adult is now 6 hours 5 minutes—but then I’m not considering that I spend the majority of my working week at a desktop computer of which my phone’s report has no knowledge, pushing me well above the daily average. The prognosis for excessive screen time is unsurprisingly not good; reading an online article on the subject is like reading the large print of the common side effects in the warning section of a drug pamphlet telling me I’m at risk of mental health disorders, digital eye strain and obesity. But there are no guidelines, no caution label, no advice to only use as directed. No label stating risk of overdose and addiction. The article is scientific in tone, and vaguely focussed on the physical wellbeing of the individual user. It doesn’t tell me much about screen time’s effect on the soul, society and the shared cycles of communication we engage in on a daily basis.

Watching Luke van Gelderen’s HARDCORE FENCING (2023) for the first time, I was transfixed to the spot. Like a house fly caught in one of those pheromone-spiked sticky traps, I was unable to break away, its mechanisms of variable reward holding me in place. As I went on the journey down its dark algorithmic path, I felt the familiar sensation of being locked in a doom scroll, automated and addicted, I was left with an uncanny yet familiar sense of seeing the world through someone else’s eyes. The film distilled and presented back compounded fears and anxieties I have had about life in the post digital era and the conflicted feelings I have about the power of online platforms as spaces of social discourse and socialisation.

<A man sits at his computer, cigarette clasped in hand, and begins to cry. He clicks his mouse three times. He can’t help it. A torrent of messages of both hate and support scroll endlessly across the screen. Behind him sits a black box which reads the words ‘YouTube Gaming’. A silent observer.>

In a conversation with a friend, I animatedly shared my experience of the potent affect produced by the film; the dizzying whirlpool of self-help rhetoric, male aggression and hyper-individualistic sentiments. We discussed the video’s deft collating and editing and the emotional qualities it exposed and forced us to analyse. So many of the face-to-camera clips felt like the creators were grasping at their “true self” in the dark. On top of the clear inner-uncertainty expressed, I questioned the validity of some of the more heightened emotions shared on screen, noting the theatricality of some of the reveals of the soul, and querying the authenticity of the more acute distress signals. ‘Some of it is just so fake!’ my friend exclaims, his expression contorts viscerally as he gets the words out, physically recoiling. It’s hard not to note the heightened sense of ‘performativity’ throughout. I agreed noting some of the performances often went too far in their bid to convince and be certified as ‘authentic’, straying into the territory of ‘cringe’. In this unsympathetic questioning of the truth and validity of the emotional content, we quickly digressed into language that creates competition among individuals; online spaces have becomes arenas in which ‘authenticity’ is judged by a network of unknown users, and depending on how the sincerity or irony of the performance lands, the audience casts judgement on whether this is ‘based’ or ‘cringe’,1 first class or second rate, authentic or disingenuous. The problem is, despite cruel dismissal, weaved through the rotation of performances to camera and emerging from behind the masks are very real sensations of alienation and fragility, discontent, and extreme anguish.

Authenticity is performed, it requires an audience. The idea of it is embedded in how identity is played out through digital technologies, and digital technologies have affected both the nature of identity and its socio-cultural function. Barbara Cueto and Bas Hendrikx observe how online spaces have encouraged a division of ‘self’ into multiple online identities and avatars which exist apart from the corporeal experience in the physical world.2 Badges of authenticity or verification populate the pages of celebrities and brands, ultimately granted to them by their followers. This embedding of self into an online proxy persona acts much like a shield or a mask, from which we can curate the aspects of ourselves which will please our audience the most.

In the physical world, masks have long been objects in anthropological history. They reify the desire to outwardly perform an alternate, and often more powerful, identity—first used in ancient rituals and practices. But a social profile on hegemonic platforms is often created in the desired image of our “true selves”, and this changes the dynamics of its socio-political power. The recurrence of the masked figure in van Gelderen’s film exposes a contemporary discomfort and malleability within our identities, the mask acting as both an impermeable barrier to the external world and a blank surface from which we can project a new identity. Social media has offered a digital extension of this which allows us to reach a larger audience. The removal of immediate physical presence means the image projected can be carefully controlled, but is subject to a greater volume of intense public scrutiny, where there is less culpability for malicious actors. It offers a channel of transmutation, allowing us to embody and reflect back the perceived ‘desires’ of society, in a bid to solicit a response from the external world.

<The figure of a woman walks towards the camera, her face obscured by a motorcycle helmet with cat ears, a chimeric cyborg with a reflective screen-like visor, she suspended in silence.>

But what happens when these masked figures emerge from the symbolic realm? ‘Reality’ artist Signe Pierce’s film American Reflexxx (2015) demonstrates this transition of avatar back into corporeal body in a shocking piece of performance and intervention by way of social experiment, and it leads to a violent end. Pierce, accompanied by videographer Alli Coates, exposes the paradox of this untenable figure being accepted in society. Dressed in a silver mirrored mask, high heels and a short blue dress, she walks the party strip of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina as a cyborg, silently and provocatively. The resulting crowd quickly turn from curious to abusive to violent, the angry mob questions her gender, displaying misogynistic, transphobic and xenophobic behaviours and ultimately is Pierce assaulted by a young woman.3 It is reflective of a violent hive-mind cruelty that exists in online spaces, a strike of a fist to keep one in check, a barbed comment to spark a frenzy of outrage, a blow to the mirrored mask.

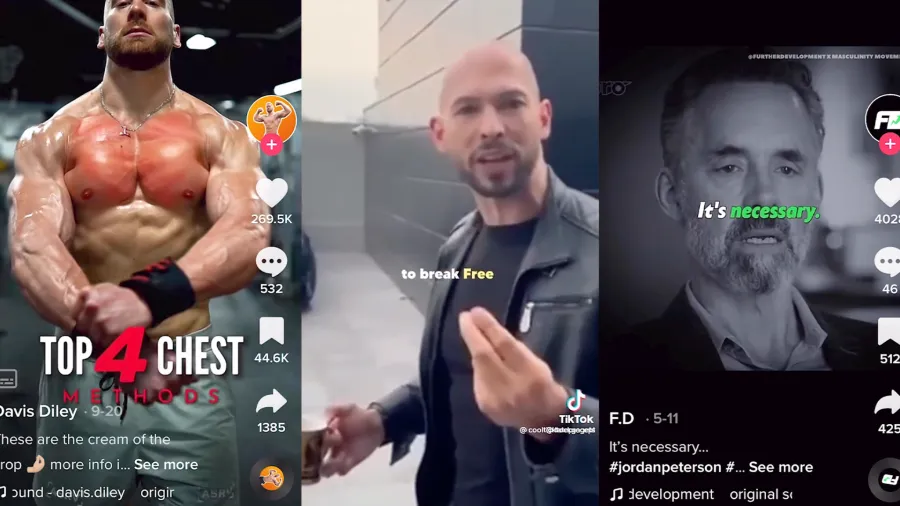

<Three consecutive 9:16 frames spin reels marked with ‘self-improvement’ and ‘self-help’ hashtags. Masculine Speech accounts, Jordan Peterson memes, and scenes of hyper masculine bodies encouraging gym culture come to the surface. In the centre is a high-pitched and accelerated monologue from Andrew Tate, his helium warbled voice encouraging ‘losers’ to get up off the couch, reminding us in ascending scales that we’re ‘in competition with the entire world!’>

Social media has become a multifaceted system—one of social labour, public theatre and an infrastructure of surveillance. It has also become the arbiter of power.4 It exists in a world with an ever increasingly sharp wealth disparity, an increased demand for unmediated authenticity, a pressure to ‘be oneself’ capitalised on by corporate advertising; it is a system which forces you to express yourself ‘and then holds you accountable for whatever you say for years.’5 Hooked to the slot-machine like cascading videos, the source of a growing discontent within ourselves, we seek within the very space of our addiction for a way out through the self-help accounts. Perhaps it is here that we’ll find some of the answers that should have been on that warning label, maybe even a recommendation for a different drug. The red pill, you say? I sometimes struggle to understand how figures like Andrew Tate and Jordan Peterson have come to fame, but when we look to how they use online platforms to tap into (and monetise) this uncertainty and disenchantment, specifically in the male ego, offering themselves as authentic trailblazers against the systems of power which have led to this deep discontent, perhaps it’s not all that surprising.

The pendulum of hate and support on social media platforms, the creation of an ‘us’ and a ‘them’, is valued through a points hierarchy which encourages outrage, deepens social divides, and like all addictions, encourages self-destructive behaviour. Identity is something we construct from the tools of communication we have to hand, the screen has become the site from which flows variably reward system, standardising and ordering the

interactions of its users in tiered system of likes, comments and shares to keep them hooked.6 ‘In the digital age, power is no longer the holder of reason and law, but the Master of Noise. The exercise of power is based on media simulation and nervous stimulation.’7 Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi identifies this slippage of our grasp on ‘truth’ and rational determination as a symptom of being subject to the accelerated flow of information. The intensification of nervous stimuli through the language of advertising creates barriers for rational decision making which previously was a slow conscious act based on examination of a limited number of sources. He describes the impact as a decomposition of the social brain, the death of social critique. For Berardi, advertising has become the defining language of the mediascape, and the cause of a cultural regression.8 For Big Tech and Big Business, it doesn’t matter as long as users keep producing data which can be harvested to keep them spending,

and so the cycle continues. However, we can’t expect to exist in this endless feedback loop unchanged.

<A group of young men stand in a sparse concrete yard, muscular and shirtless. One boy tenderly kisses his friend—who holds a fold-up chair—on the cheek, before downing what’s left in a bottle of booze and taking the last drag from his cigarette. The sound of the bottle smashing on the ground is audible just as he leans forward waiting for the chair to come crashing down.>

HARDCORE FENCING is punctured throughout with words and acts of self-violence, these moments are always staged, and where some feel like explorations, others feel enforced. For Berardi, these concepts of ‘identity’ and ‘authenticity’ that seem to preoccupy us, do not even really exist. Instead he recognises that it is a nostalgia for authenticity, and a culture which idolises it, which is very real. He writes ‘identification may be viewed as an attempt to stabilise the self in its relation to the outside reality.’ However this attempt to self-stabilise denies the nature of identification as something that is in flux, he claims, any attempts to stabilise identity turn into acts of self-violence, and ultimately aggression. He goes on ‘fascism is the obsessive and aggressive enforcement of that provisional stabilisation.’9 The implication of this sentence when applied to the potential of the hive-mind as system of control haunts me. It’s hard to know what the way out of this is, or what the counterculture should look like. Perhaps it is to be found in ‘the dark forest’ region of the web, these smaller networks made up of platforms like Discord, Substack, Reddit and Telegram are arguably free from the homogenisation of mainstream social media, although these are not without their problems. Or maybe its offline entirely.

As the insurmountable and unrelenting pings, vibrations, alerts, and notifications on my phone increase in frequency, I want to be online less and less. As someone who often craves the space of social critique that Berardi laments, I find exhibitions some of the few places left that allow for the distractions of everyday life to melt away, my last vestibules of uninterrupted focus. A few months into Trump’s Rupert-Murdoch-backed presidency, and in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, I walked the airy white exhibition halls of the often controversial Whitney Biennale and came across the work of Frances Stark for the first time. Eight giant canvases transcribed in paint the words of punk musician Ian F. Svenonius’s eponymous polemic text Censorship Now! It felt timely then, it only feels more so now. The text argues that art has become impotent and irrelevant under an American militarised state, lost meaning at the hands of the super privileged and has become oppressed and disarmed by capitalism. Svenonius—since responsible for his own cancellation10—laments the time where people recognised the power of art, and proposes artists should take control of censorship and eliminate everything from the press, to mass-produced pop, technology, and expressions of fascist ideology. He marks art and media as dangerous substances that must be regulated, as well as placing their use as a beacon of hope in the hands of artists. It’s punk. It’s idealistic and extremist. It’s ironic and absurd. Stark paints the words large so the pages of the book fill the gallery walls, the biting and snippy prose tower above, some sentences underlined in dripping red paint referencing wars which have taken place at the hands of the state whilst it patronised the arts. Alarming double exclamation marks fill the borders where there are calls for mass censorship. For all the text’s possible shortcomings, it demonstrates and recognises the true political power of media and calls for a sense of responsibility in linguistic and creative expression. Stark simply enlarges key pages, calling our attention. The uninterrupted moment with the work lets us consider the polemic deeply, moments of outrage are followed by moments of rational and the critical brain kicks in.

Much like Stark, van Gelderen calls our attention to some extreme content, magnifying key moments that together tell a more complex story. The compilation allows the moments of outrage–which often emerge from watching a short form clip–wash over so the bigger picture starts to emerge. And it’s dystopian. Embedded within its content is a very current mood of social alienation, entrapment in a false economy of ‘authenticity’, and the seeds of a rise in extreme right-wing politics. But it also lays out some useful ways to think about our increased dependence on media technology, how processes of identification and authentication are becoming increasingly political, how methods of communication have become embedded in a language of advertising and capitalism, and how this is negating space for rational decision making. Lifting reactionary content from the very platforms which Berardi believes to have led to the decomposition of the social brain, and positioning it in a context which makes space for social critique, allows us time to see what’s really at stake.

Sadbh O’Brien is an artist and writer based in Dublin.

This text was written by Sadbh O' Brien in response to Luke van Gelderen's — Romeo Save Me, the penultimate exhibition of our 2024 Artist-Initiated Projects programme. You can read more about the exhibition here.

Please find a print format version here.

Notes

1 Nate Sloan, ‘Beyond Based and Cringe’, Do Not Research. 21 June 2021. https://legacy.donotresearch.net/posts/beyond-based-and-cringe

2 Barbara Cueto and Bas Hendrikx, eds., AUTHENTICITY? Observations and Artistic Strategies in the Post-Digital Age (Valiz, 2017).

3 Alli Coates and Signe Pierce, ‘AMERICAN REFLEXXX’. 7 April 2015, Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bXn1xavynj8&ab_channel=AlliCoates%2BSignePierce

4 Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, ‘Trap of Identity and Delusion of Truth’ in AUTHENTICITY? Observations and Artistic Strategies in the Post-Digital Age, eds. Barbara Cueto and Bas Hendrikx (Valiz, 2017). p138.

5 Caroline Busta, ‘The internet didn’t kill counterculture—you just won’t find it on Instagram’ Document Journal. 14 January 2021. https://www.documentjournal.com/2021/01/the-internet-didnt-kill-counterculture-you-just-wont-find-it-on-instagram/

6 Brad Troemel, ‘The Culture War Report’ 30 January 2022. Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DIJXeIov5Y&t=1s

7 Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, ‘Trap of Identity and Delusion of Truth’ in AUTHENTICITY? Observations and Artistic Strategies in the Post-Digital Age, eds. Barbara Cueto and Bas Hendrikx (Valiz, 2017). p138–40

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Evan Minsker, ‘Ian Svenonius Publishes and Deletes Post About Being “Completely Inappropriate to Women”’, Pitchfork. 27 July 2020. https://pitchfork.com/news/ian-svenonius-publishes-and-deletes-post-about-being-completely-inappropriate-to-women/